That's it!

It's been a fantastic summer of exploring what it really means to be an artist through this project. One thing that I have not talked about in my blog was the writing process for creating Genesis, and I suppose that is because it is a hard thing to describe or explain with real clarity. Especially in talking about poetry. One of my favourite poetry critics, David Orr, of the New York Times Book review said poetry is more like a place that you go and explore than something you, as a reader understand. Poetry, he says, is more like Belgium. If you are going to Belgium you don't memorize the phone book to understand the culture. Instead, you hang around and enjoy it, learn about it through being with it and in it.

When I was setting out to write this chapbook, I wanted to write about fish because fish are a very rich cultural symbol. Fish are often said to symbolize fertility and abundance, birth and rebirth. The journey of exploring this metaphor, translated more into an exploration of myself and the season of my life that I am in. As a collection of poems, I was surprised at how things came together. I feel, now that the book is complete and printed, that it was really an act of coming into adulthood in some ways. The process helped to teach me how to take a thought or idea or image, and explore that thing, and even now I feel like I only just scratched the surface.

It was an absolute pleasure to work with Briar Craig this summer. He is a very generous teacher and an incredibly talented print maker. Likewise, it goes almost without saying, that it was a pleasure to have Nancy Holmes as my supervisor for this project. I am so lucky to have such talented teachers, who have supported and mentored me.

I will be launching this book as a joint launch and gallery exhibition with another book that I worked on in the past year. The show is called Baptism - A Happening and will feature Daylighting (a collaborative book of poetry about Rutland, (Kelowna) written by myself and Sarah Megan Hunter), Genesis, and artworks that were inspired by these two chapbooks. Baptism - A Happening will be taking place in the Alternator Centre for Contemporary Art, here in Kelowna, and the opening will be held on October 3rd, 2014.

A Summer of writing, creating and exploring the world of fine and small press publishing.

Monday, September 15, 2014

Monday, September 8, 2014

Book Binding round 2: Hardcover Books

On the course of building my books, I did three different covers: 2 soft cover (with different colours of paper) and a hard cover edition. Here are some instructions on hows to make your own hardcover books!

Lay out the pieces as shown in the above image and cut the cover paper so that it is easy to fold and glue.

And away you go! This method is very similar to the one I used for the other covers, and just as before nows the time to put your book under some weight and leave it over night so that the glue can set. Presto! hard cover books!

The first thing that you need to do when creating a hardcover volume is to find a material that will sit under the cover paper to give it the desired stiffness. For my books I used mil-board, but you can use just about anything that is hard and flat, like cardboard or wood or what-have-you. Then you cut two rectangular pieces for for the cover and one thin rectangle for the spine. The rectangle for the spine should be the same width as the width of the book when it is laid flat.

Glue down cover paper and smooth with a bone folder. Then get your text block signature that you want to go inside and glue down the outer sheet.

And away you go! This method is very similar to the one I used for the other covers, and just as before nows the time to put your book under some weight and leave it over night so that the glue can set. Presto! hard cover books!

Thursday, August 28, 2014

Now We're Almost There

Alright, it is August 28th, and the project has almost reached it's exciting finish. I can now safely say that I have created 25 copies of my book. It was a big crunch to get everything done before heading to Calgary for the last week of August, and I didn't quite make it; there is still some final gluing that needs to be done in the next couple of days. That said, the text blocks for each book have been folded into single signatures, bound and editioned, and the covers are folded and ready to be glued.

Using screen printing has been a really interesting way of making this project happen. Initially I was going to do the whole book in "duo-tone", meaning I would be using two layers of ink. After, doing some tests of the second layer of ink I decided to keep this only for the images because properly registering all of the pages of text would take more time and paper than I have. Mostly paper. Have I mentioned this before? I know I have. Starting any printing project means using way more paper than you would expect. Doing the whole book in duo-tone would mean making twice as many first layer prints or more with the expectation that on the second layer, I would probably waste half of my attempted prints. Anyway, here is a quick pick of how one of the images turned out.

After getting everything folded, I bound the signatures using a 3 hole bookbinding stitch, using bookbinders thread. Super simple but it did the trick.

The outer sheet of the signature will become the inner part of the cover once the books are all glued together. Here, I used some beautiful mulberry paper for two reasons: 1) it is super pretty (obviously!) and 2) Mulberry paper is really strong and archival quality. This is because the mulberry fibers that are used to make the paper are very long. Because this paper comes in the wrong size for what I was doing I had to trim the paper. I did this using water and tearing it rather than cutting it to size because I wanted to keep the nice edging on the paper.

I also glued the covers together, so now they are are all ready to be put together with the text block. To do this, I used some small Litho stones that we have in the print shop for weight.

Tomorrow, I will be heading back to Kelowna and back to finish with the final gluing of everything. Onwards!

Wednesday, August 13, 2014

10 Things I Have Learned: a bookmaking list

The internet has inspired me to make a list.... with pictures!

(and I stole them all...)

1. As with life, anything that can can go wrong, probably will.

2. You will run out of the paper that you want the most.

3. You will be unable to find satisfactory paper and will have to either order online, or get crafty.

4. You will feel like you are using an entire forest worth of paper.

5. There are a million ways to bind a book, pick one.

6. The simplest binding is the best binding for short books in large quantities.

7. Have a REALLY good mock-up of your text block. Without this, likely you are either a computer or your pages are everywhere.

8. Measuring and cutting will take twice as long as you think.

9. Always work on a clean surface, because once there is stuff on your paper, that't it for that paper.

10. If you are using letter press, make sure there is enough type for what you need it for, because you will run out of that too.

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

Book Binding At Long Last!

At last! I have reached the Promised Land! Today is most definitely the first day that I have really felt like I am making books. Now that I have gotten together many of the materials that I need, and I know which direction (sort of) that I am going in, I can start actually making books.

Today, I assembled two different books, filled with blank paper to practice before I settle on a design and work away at the text blocks to fill them. As I mentioned in my last post, I will unfortunately have to give up the ghost of lead type for my text block. Instead, I will be doing the entire book using screen printing. The initial image of the text will be designed and typed on a typewriter and then transferred to screen... but that whole hurrah will be discussed in a different blog post!

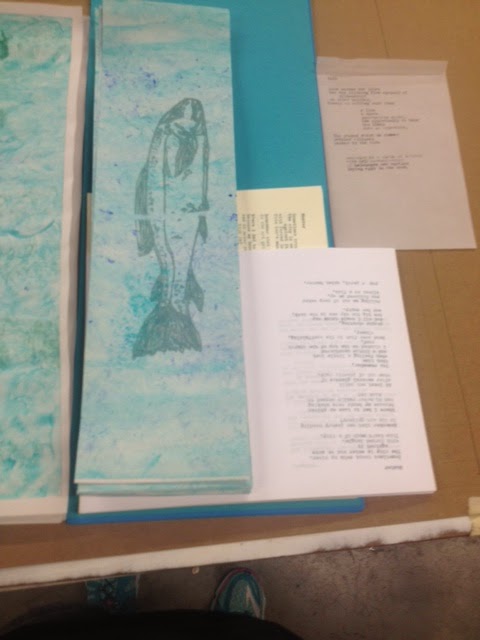

The first book is a folded "soft-cover". The cover is made with a light card, called Casan Mi-Teinte turquoise, that I folded and attached the would be text block (in this case blank pages) to. I cut and pasted one of the screen print fish that I designed for the cover onto the card before folding.

Next, you get the "text block" ready. I did this binding the text pages together, or the guts of the book shall we say, using a simple 3 hole pamphlet stitch. You can find super easy instructions for that here (this is the site I used!).

Today, I assembled two different books, filled with blank paper to practice before I settle on a design and work away at the text blocks to fill them. As I mentioned in my last post, I will unfortunately have to give up the ghost of lead type for my text block. Instead, I will be doing the entire book using screen printing. The initial image of the text will be designed and typed on a typewriter and then transferred to screen... but that whole hurrah will be discussed in a different blog post!

The first book is a folded "soft-cover". The cover is made with a light card, called Casan Mi-Teinte turquoise, that I folded and attached the would be text block (in this case blank pages) to. I cut and pasted one of the screen print fish that I designed for the cover onto the card before folding.

The important thing with this type of cover design is that you want the length of the paper that will become your cover to be twice the length of the final cover size so that you can for it in on itself. I wanted my cover to be 12" X 9" so the paper that I am using in this pic is 24" X 9". Make the first fold directly in the middle of the paper. Next, measure and mark 6" from the center fold on either side. Fold where these marks are "hamburger"-wise as the kids say, or in layman's terms parallel to the first fold. This is your cover.

Finally, take your guts and glue them to the two inner flaps using pH neutral binding glue. (The glue is important because other things will degrade over time eating away at the paper and all your hard work). The inner sheet that I used was a scrap of mulberry paper.

After all that's together, you may also want to press the book under something heavy. Unless you happen to have a bookbinding press lying around, which we just happened to have at UBCO, you can really use anything heavy for this: a cinder block, Michelangelo's David, you know, whatever you happen to have kicking around that will allow it to lie flat between two flat surfaces that cover the entire thing with pressure. If it's not totally covered you might end up with some kinks in your beautiful cover and we can't have that now.

As for the learning experience today, I will be doing some more screen printed fish in a lighted contrast with more translucent ink to see how they look compared to the stark grey and black I used on the last ones. Also, I have come to the conclusion that I will be doing two editions of the book... one soft-cover and one hard cover. Stay tuned for next time when I explain how I will be constructing the hardcover versions of my book!

Tuesday, August 5, 2014

Printing Experiments Part 2: Converting an Etching Press for Type

Last week, my blog post discussed using the Adana Letterpress, courtesy of UBCO, for printing my book, and after some deliberation I came to the conclusion that the small printing surface that the Adana has would take too long to print my 24 page book of poetry. So this week, I am going to talk about how to convert an etching press into a flat bed letter press.

This is one of the UBCO etching presses.

The way that an etching press works is the heavy metal cylinder roles back and forth over the printing material to make an impression. The impressing surface lays on the flat bed that moves underneath the cylinder, then the material that is going to take the impression sits on top of that covered with padding that is most often made out of thick felt sheets. These felt sheets are intended to protect the metal cylinder and form around the paper and impressing material (in our case lead type) making a nice even impression.

The felt packing is really important because, when printing, I want to make sure that I am not damaging either the press cylinder or the lead type. If the cylinder is sitting too low it will crush the type, so the brass nobs at the top that control the distance between the bed of the press and the cylinder need to be just right.

The felt packing is really important because, when printing, I want to make sure that I am not damaging either the press cylinder or the lead type. If the cylinder is sitting too low it will crush the type, so the brass nobs at the top that control the distance between the bed of the press and the cylinder need to be just right.

In order for us to use the etching press, we first needed to find a tray that is the right height for the lead type to sit in. Luckily, Briar had a couple of these such trays hanging around for us to use. Next, we found and cut a wood board to the right size so that the tray with the type in it can sit down into the flat bed. It looks like this.

After that we were pretty much done and ready to set type using the same kind of system that we used in order to set type in the Adana, utilizing the sides of the metal board just as we used the chase in the Adana, to brace the type, furniture, and slugs.

Luckily after talking to the UBC Okanagan faculty about this particular hiccup the school is looking into buying a whole bunch more stock of lead type, furniture and drawers to use in print making! I can't tell you how exciting this is -- especially since I will hopefully be continuing on with more printmaking in September. All that said, we are still currently at a loss for type and the type that the school is buying is going to take about a month to get here. Which means that it won't be here in time for me to finish this current project.

All that said, the moral of the story is that I will now be filling the text block using screen printing. Which in the long run should take less time and will let me add sketches as well to the body of the work. It's all very exciting. Below is a sample of the first screen prints that I have done. These fish are going to be used as cover art.

All that said, the moral of the story is that I will now be filling the text block using screen printing. Which in the long run should take less time and will let me add sketches as well to the body of the work. It's all very exciting. Below is a sample of the first screen prints that I have done. These fish are going to be used as cover art.

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Printing Experiments Part 1: The Adana

This summer has been an adventure in the realm of bookmaking, and, as per the norm of my blogging aspirations, I have not been recording them to the best of my ability!

The last few weeks I have had the absolute pleasure of working with lead type at UBC Okanagan's campus. UBCO is home to both Briar Craig (from whom I was able to post snippets of an excellent conversation we had in an earlier blog post) and an Adana model M0120-M0125 printing press.

The last few weeks I have had the absolute pleasure of working with lead type at UBC Okanagan's campus. UBCO is home to both Briar Craig (from whom I was able to post snippets of an excellent conversation we had in an earlier blog post) and an Adana model M0120-M0125 printing press.

But before I could really get started with using this little beauty I had to go about organizing some of the new type that I was thinking of using (Neon Century Schoolbook 12pt) into a type drawer. There are different ways of organizing your standard type drawers. One of the most common arrangements is the "California Type Case" that is set up as follows:

So, I went about organizing the new set of type into a drawer. Interestingly, word "Neon" in the title of this font is an indicator of the specific typesetters that designed the font -- in this case the Chicago Typesetters. The word neon was added to the title to avoid copyright infringement on type of similar design. Our print shop at UBCO has both Neon Century Schoolbook and Neon Helvetica (both in medium 12pt as well as a set of Neon Helvetica 24 pt).

Once this was done I could start setting type. At this point a typesetter starts to set the type using a composing stick. Like this:

On the bottom, ledge part of the composing stick the typesetter first needs to put down a "slug". The slug is a piece of lead that the type is set onto. It acts as the spaces between lines and stops the letters from falling all over the place when you move the type off of the composing stick and into the chase. The chase is a metal square that the type is set into and tightened using block of strong wood (like oak).

Setting the type and getting it to stay in the chase takes a long time, and this particular model of letter press can only do about a half letter size page of text. Which is fantastic, if you have a lot of time -- like a lot of time. It takes about 4-6 hours to set a page of type, and proof it. It takes another fair chunk of time to get the machine properly set to print consistently, through the use of rigging up bits of paper and other little shims and things to get all of the letters to print, and finally, printing your finished copies. That's the easy part, once you have done all that set up, printing on the final sheets of paper is a breeze... providing you get everything all inked up properly.

For my test run, I decided to print one of the poems from the book I am publishing for this project, called String Men. Here's a sneak peak!

After creating the mock up for this project, I have organized my twelve poems so that I will be printing a text-block comprised of 24 pages. A 24 page text block breaks down to 12, 2-page plates, with 2 plates on each sheet of paper. Which means that the text block will consist of 6 sheets of paper. This is a huge endeavor for a little press. Setting one day per page and printing one day per page means, 2 days for each page. Meaning the shortest possible print time is 48 days. Based on this, the next thing that I am going to try is to convert the print studio etching press into a flat bed press.

Stay tuned for Printing Experiments Part 2: Converting an Etching Press!

Monday, July 7, 2014

Interview with Briar Craig

Briar Craig is the associate professor of printmaking at the

University of British Columbia Okanagan. He focuses primarily on screen

printing, and has a love for typography and text that he incorporates into his

work.

Recently we got together to talk about print making, art books, and topography:

JB: You have said before that print making is making a number of originals instead of copies, can you tell me about that?

BC: It’s a difficult distinction to make when you are talking about text because of course once you’ve got lead typeset you can print forever and it’s really not going to wear out very easily, so you can print unlimited things where as print making does tend to be about the limited edition in a way. From my perspective anyway. Certainly I have the capability. The technology we use in screen printing for example, is capable of printing thousands of things, but why would you do that? I think there is a kind of fascination with printing technology in terms of printing text. I mean there is a fascination about printing whatever number you need and, because you tend to be printing one thing at a time, it’s not filled with different colours and things like that. It might be, but it doesn’t tend to be. Once you get the type set, or the litho plate exposed, or whatever you can just print until you get the number you want. Whereas with layering prints, to make images you start with a certain number of pieces of paper and you print all the black or all the yellow or all the red or all the blue and then once those are done and dry then you print the next colour and if you screw up that one’s gone. It’s just out. So, if you start with 10 sheets of paper you might end up with only three prints that turn out and the other seven might have failed for one reason or another. So, the process itself of building images does tend to foster a limited edition kind of mentality because there is no way you could start with a thousand sheets of paper. Not only would it be expensive, where would you put them as they were drying? Whereas with letter press stuff, it tends to come off the press almost dry, so you can stack things if you need to. I mean, it’s not the ideal thing to do but it can be done.

JB: That said about print making, how do you feel about art books? Because there is this whole movement towards the book as art, or art books, do you think of them as originals or do you think of them as copies?

BC: Well, again, I think that it’s multiple originals. I mean, even when we talk about multiple originals in print making there is idiosyncratic differences between them all. There is also a thing called the “edition varie” [edition Ver-y-Ah] where you can have a hundred images that have the same component parts, but they are all put together maybe slightly differently, or the colours change, or there’s a shift in some way. I tend to think of the book as that. If you print a limited edition of 10 books, or 400 books they’re all going to be slightly different but they really contain all the same information. So, I see them as the same.

JB: Would you number the books as one print run even if the colours were different and that sort of thing?

BC: You could, yes. Some limited edition books are editioned. I mean chapbooks, and things like that. They aren’t printing massive numbers. I don’t know if they are editioning them, but I still see them as the same as a print. I think a lot of the same interests are shared between publishers, people who are making limited edition books, and print makers. We are interested in the feel of it. We’re interested in the look of it. We’re interested in how inks sits on paper and all those things are aesthetic concerns that I think the artist and the book designer all share. We all share paper and we all share ink, and pressure to some extent. Those things have very visible manifestations and I think those are the things being honoured now more than they were maybe 20 or 30 years ago.

JB: Yes. It’s like you were saying earlier about the difference between the desire to imprint or not imprint the paper with the printing press changing over time and as we have moved to the digital, the desire for that indentation that comes from using lead type has become popular because it equates to authenticity. I’m just trying to collect my thoughts here, I haven’t done much in the way of interviewing before and I am fairly non-linear thinker.

BC: That’s a good thing. Because I am so linear as I am sure you can tell and I think you have to be when you are dealing with a process oriented thing but I think that print making is about understanding the process and feeling the process rather than memorizing a recipe. It’s not like once you do this, then you do that, then you do that, once you get it you just do those things and you don’t really think about it in a linear way. It just makes sense.

JB: Kind of like how you might use a poetic form and within that form you can just go with it and do whatever you want, but there is still a method?

BC: Yeah and you can throw out the rules and say ‘well I’m going to try this different way’ or ‘I’m going to reverse these two steps and see what happens’. As long as you understand what those steps do you can go back and fix things if you have to and sometimes I think that it is really just fun to play with the materials and see what kind of accidents happen. As an artist making images I do tend, I am sure you have heard me talk before about this before; I have said this before; I am in collaboration with the process. I am not sure that painters, drawers, sculptors feel as in collaboration with their process. Lithography in particular can do awful things to images, it can also totally change your intentions, but if you are open to seeing what happens through that it might better than expected, and it also gives you something new to work with, something unexpected to work with. That’s what keeps it interesting.

JB: Would you consider it more avant-garde than other art forms? Like moving towards enjoying the process more than your desire for the finished product?

BC: It’s funny. I think one of the slams against print is that it is so technical and you have to know beforehand what it’s going to turn out like and I don’t believe that to be true. I think that if you think you have got an idea in your head and you’re going to make it then yeah it is going to be a technical struggle to make the process do exactly what you want but and in some ways it is kind of a weird thing in school because we have to teach people from that perspective at first, you have to take control of this. But once you have control of it once you understand it, it’s not bad to sort of screw with it a little bit and see what happens because then every stage of the development of an image is something that you are having to figure out and that keeps the creativity alive. A painter might say every brush stroke has to be creative. Well, yeah we have to be creative too but we also have to think in layers so we have to be creative every time we’re making an image for every layer. So, I don’t see the process as somehow imposing something on us. It is a collaborator and it is something that likes to mess with us sometimes and sometimes it does exactly what you want and you’re thrilled. Then other times it’s like whoa what the hell happened there? But, hey, that’s kind of cool. Or oh my God, I have to start again.

JB: I just relate it all back to poetry so often because that is what I do, and I think that it’s totally like that. I mean thinking of the poem as being a separate entity or like having its own kind of personhood and you just kind of explore that.

BC: Yeah. I can’t imagine knowing what exactly what something is going to be and then taking the two weeks to a month to make it be exactly that. How boring would that be! My work is really controlled in a lot of ways, I do have a pretty good idea of how it’s going to turn out but I’m really more interested in the nuances of the things that don’t go the way that I expect and the scrambling you have to do to make that still work, because once you have invest 4 weeks in an edition of 10 prints and something doesn’t go exactly the way you expected you have to figure out how to make that work so that you can still live with it.

JB: It’s definitely not like at that point you can scrap the whole thing. As a lover of type and typography do you ever see yourself incorporating pressing (with or instead of screen printing) into your work?

BC: It’s more of a scale issue right now. Screen printing allows me to print very larger in a very small studio like we have, whereas letterpress is really made for things like small posters. They’re not really made for gigantic things, and that’s where my interest tends to lie. In larger scale. I think it’s maybe because I am large too. In the end when I stand back and look at a print that is really large, I stand back and I think ‘oh, wow, yeah, that’s really nice’ and when I hold up some little thing, and I go ‘oh look what I did’, I feel like an idiot. But having said that too when I was in Regina over this sabbatical, they were just donated this past year, a fair number of wood type and metal type at a very large size and so I was printing off entire alphabets just to have a visual record of the imperfections in the alphabet. I printed a light version of each and I printed a dark version of each and a kind of a scrappy in between version. Now, I am able to scan those and I will be able to use those to make whatever size text that I need for screen prints, so that I will have the visual qualities of the letter press, but it will be printed through screen. I won’t get the embossing sadly.

JB: I know people can build their own font. Would you ever consider building like giant font sets?

BC: We’ve got this laser cutter now, and it engraves things, so if we can get some wood, good enough quality wood we could engrave wood type. Storage is always the issue, but yeah I am totally keen on that.

JB: That’s so awesome.

BC: Yeah, when I was at Don Black Linecasting (http://www.donblack.ca/) in Toronto a couple of years ago, he, or they, were so excited by this company in the states that was cutting wood type again and they were doing it with a digital router, but now the laser cutter seems like it’s way easier to get absolutely precise edges and things.

JB: Then you can do whatever kind of font you want, as well.

BC: Yeah, and it doesn’t have to be on a perfect piece of wood as well. As an artist I am more interested in the imperfections of a surface whereas buying new font they are more interested in having no imperfections on the surface because they will get dinged up over time. I would just get crappy wood so whatever you have on the surface of that crappy wood is what you end up printing and that’s kind of cool too.

JB: So, my next question then is, what’s your favourite font? I know we talked Helvetica at one point.

BC: Well, I’m in awe of Helvetica just for its clarity. I know that, what is it? Arial, is the windows versions of Helvetica but it’s not as nice. There’s something about it that just seems a little wrong. I’m not even sure I can really say what. So, I am in awe of Helvetica and for certain things like labelling, shipping labels and things like that Helvetica is the best because it is so easy to read. I have to say boring as it sounds Times New Roman. But Garamond is my all-time favourite because it really feels old.

JB: What is that you like about Garamond as a font that you relate to verses Helvetica which is great for shipping and packing and clarity?

BC: There is something about a kind of nostalgia to it. It feels old, it’s much more cursive. It’s a serifed font and the little loops and bends on the bottoms of the letters have a really nice almost scriptive feel to them. So, for me it’s clarity with the flair of the handmade somehow.

JB: How do you feel about people that might say that Helvetica is like the serial killer of fonts?

BC: (Laughs) Well, I think the criticisms we level are reflections of our inner selves. I have never heard anything about that! Then again, I do remember seeing a couple of years ago there was a documentary about Helvetica out and it was on PBS and it was two hours of just font, Helvetica in it’s different forms and I remember I had never realized that there were so many different forms!

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

Death & The Future of Publishing (my summer project)

The future of the book is tenuous these days; The advent of e-books have created a publishing climate where anyone can publish books with a wide distribution for little to no cost. I, as a hopeful writer, and aspiring publisher have been bombarded by cries of "publishing is dead", and sure, things cannot go on as they are in this world with everything growing, and changing in the technological storm of capitalist consumer culture, where one technology is dead in a year or two, to be replaced by a completely different beast of circuitry that is incompatible with it's last incarnation.

However, I have heard these death knells before: Punk is dead; Poetry is dead. All my favourite things, it seems, are mostly dead, and that doesn't change how lively they appear at the punk shows and poetry readings that I attend. Leaving punk and poetry aside for another day, another essay perhaps, and returning to publishing, I can't help but think that the idea of death is merely the recognition of change. Truly, we have set a course in publishing where we can never go back to the mass production of pulp romance that we have had in the past, and truly, the e-book in these circumstances are a superior technology to the old ways.

This technology, useful though it is, does not take into accounts the human desire for physical objects. We humans spend most of our lives amassing a wealth of objects through which we define ourselves. (My dear friend and fellow poet Kale Greenfield has a poem about this that has been published in a few zines and chapbooks this year called "The House, The Car, The Things" that captures this perfectly.) Books are very much a part of the need for aesthetic pleasure derived of objects, and it is very unlikely that any e-reader, no matter how fancy the cover or how high the quality of the screen, will be able to give me the same feeling that I get from the feel of a book.

So, where are we going exactly? What is the future of publishing?

My bet is on the divergence of the publishing industry into two paths: consumption and art. As I mentioned earlier, there are distinctly areas that benefit from the mass effectiveness of e-books. There is a whole market of people that read a book once and never pick it up again. Libraries benefit because there would never be such a thing as a lost book again. This is the place of consumption. It is entertainment and there is nothing wrong with it. The consumption path brought us Netflix, changing the way we consume T.V. and movies forever. This is the home of the e-book and it belongs there.

Moreover, it is the second path that I am most interested in: Art. Art is the place of the concept. It is the home of deep thought. This is where poetry lives and as a poet I know that this is the future of the printed word, in aesthetics and object glory. The path of publishing is bound to open up into the world of the fine press and the small press creating beautiful object that people will and already do covet. This path is much the same as the one charted in recent years by the music industry, where tapes and CD's have all but disappeared for digital copy, but people have come back to vinyl for its quality. Records are the art of the music industry, and the Handmade book is the future of book art.

With this in mind, I have decided to embark on the academic discovery of handmade books and letter presses as a summer project. This summer I will be writing poetry, compiling a manuscript and building a small press release of 50 copies from the ground up. This blog is a record of this project and a way of opening the discussion of the future of publishing. I will be talking about the editing process and what it means, about the nuts and bolts of printing using a letterpress, sourcing materials and the tedium of binding by hand. I want to explore also the concept of the codex, and how art books marry form and content to create something different.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)